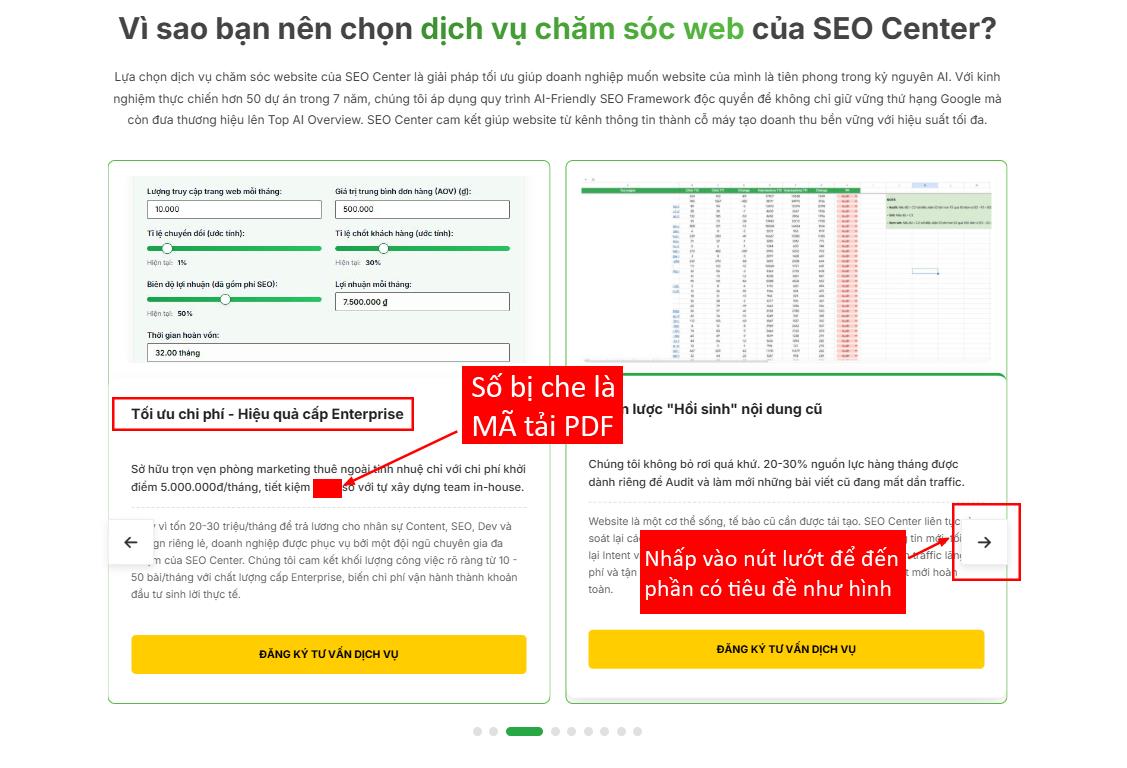

Bên dưới đây mình có spoil trước 1 phần nội dung của cuốn sách với mục tiêu là để bạn tham khảo và tìm hiểu trước về nội dung của cuốn sách. Để xem được toàn bộ nội dung của cuốn sách này thì bạn hãy nhấn vào nút “Tải sách PDF ngay” ở bên trên để tải được cuốn sách bản full có tiếng Việt hoàn toàn MIỄN PHÍ nhé!

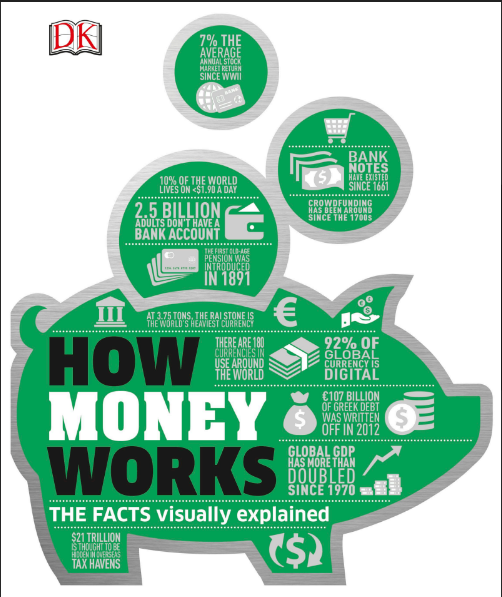

Money is the oil that keeps the machinery of our world turning. By giving goods and services an easily measured value, money facilitates the billions of transactions that take place every day. Without it, the industry and trade that form the basis of modern economies would grind to a halt and the flow of wealth around the world would cease. Money has fulfilled this vital role for thousands of years.

Before its invention, people bartered, swapping goods they produced themselves for things they needed from others. Barter is sufficient for simple transactions, but not when the things traded are of differing values, or not available at the same time. Money, by contrast, has a recognized uniform value and is widely accepted. At heart a simple concept, over many thousands of years it has become very complex indeed. At the start of the modern age, individuals and governments.

Money has fulfilled this vital role for thousands of years. Before its invention, people bartered, swapping goods they produced themselves for things they needed from others. Barter is sufficient for simple transactions, but not when the things traded are of differing values, or not available at the same time. Money, by contrast, has a recognized uniform value and is widely accepted. At heart a simple concept, over many thousands of years it has become very complex indeed.

At the start of the modern age, individuals and governments began to establish banks, and other financial institutions were formed. Eventually, ordinary people could deposit their money in a bank account and earn interest, borrow money and buy property, invest their wages in businesses, or start companies themselves. Banks could also insure against the sorts of calamities that might devastate families or traders, encouraging risk in the pursuit of profit.

OUTWITTING THE DEVIL is the most profound book I have ever read. First, I was incredibly honored when Don Green, CEO of the Napoleon Hill Foundation, trusted me enough to ask me to become involved in this project. And then I read the manuscript! I couldn’t sleep for a week. Written on a manual typewriter in 1938 by the Master himself, Napoleon Hill, this manuscript had been locked away and hidden by Hill’s family for seventy-two years. Why? Because they were frightened by the response it would invoke. Hill’s courage in revealing the Devil’s work around each of us every day, in our churches, our schools, and our politics, threatened the very core of society as it was known at the time. When asked why the family had hidden the manuscript, Don Green recites the following inside story: It was the objections of Hill’s wife, Annie Lou.

She was secretary to Dr. William Plumer Jacobs, president of Presbyterian College in Clinton, South Carolina. Jacobs was also owner of Jacobs Press and a public counselor to a group of South Carolina textile firms. Jacobs hired Hill to come to Clinton to work for him, and Annie Lou did not want the book published because of the role of the Devil. She feared the response from organized religion (and maybe for Hill’s job). Even though Hill died in 1970, Annie Lou did not die until 1984. Upon Annie Lou’s death, the manuscript.

The economic law of supply and demand states that when the price of a commodity (such as oil) falls, consumers tend to use, or demand, more of it, and when its price rises, the demand decreases. One of the key factors affecting price is the amount of a commodity available—its supply. Low supply will push prices up, as consumers are willing to pay more for something that is difficult to obtain, and high supply will push prices down as consumers will not pay a premium for something that is plentiful.

**How it works**

Bartering was a very immediate form of transaction. Once writing was invented, records could be kept detailing the “value” of goods traded as well as of the “IOUs.” Eventually tokens such as beads, colored cowrie shells, or lumps of gold were assigned a specific value, which meant that they could be exchanged directly for goods. It was a small step from this to making tokens explicitly to represent value in the form of metal discs—the first coins—in Lydia, Asia Minor, from around 650 BCE. For more than 2,000 years, coins made from precious metals such as gold, silver, and (for small transactions) copper formed the main medium of monetary exchange.

Published in 1900, German sociologist Georg Simmel’s book *The Philosophy of Money* looked at the meaning of value in relation to money. Simmel observed that in premodern societies, people made objects, but the value they attached to each of them was difficult to fix as it was assessed by incompatible systems (based on honor, time, and labor). Money made it easier to assign consistent values to objects, which Simmel believed made interactions between people more rational, as it freed them from personal ties, and provided greater freedom of choice.

The economics of money From the 16th century, understanding of the nature of money became more sophisticated. Economics as a discipline emerged, in part to help explain the inflation caused in Europe by the large-scale importation of silver from the newly discovered Americas. National banks were established in the late 17th century, with the duty of regulating the countries’ money supplies. By the early 20th century, money became separated from its direct relationship to precious metal.

The Gold Standard collapsed altogether in the 1930s. By the mid-20th century, new ways of trading with money appeared such as credit cards, digital transactions, and even forms of money such as cryptocurrencies and financial derivatives. As a result, the amount of money in existence and in circulation increased enormously.