Bên dưới đây mình có spoil trước 1 phần nội dung của cuốn sách với mục tiêu là để bạn tham khảo và tìm hiểu trước về nội dung của cuốn sách. Để xem được toàn bộ nội dung của cuốn sách này thì bạn hãy nhấn vào nút “Tải sách PDF ngay” ở bên trên để tải được cuốn sách bản full có tiếng Việt hoàn toàn MIỄN PHÍ nhé!

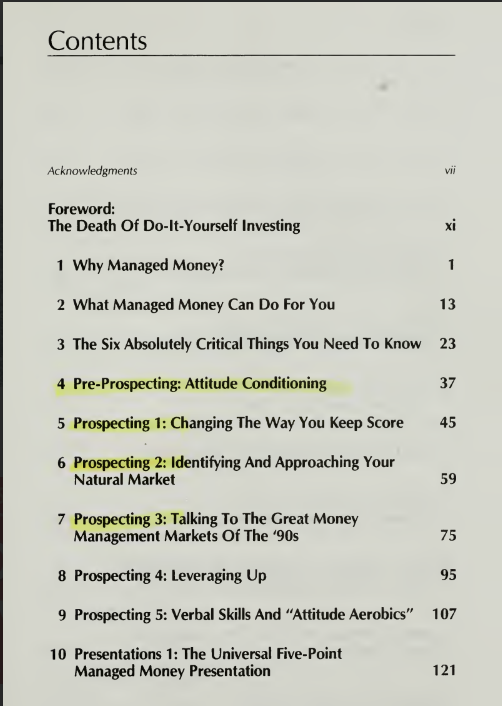

People who write books seem always to thank their families, more or less ritually, at the end of the acknowledgments. I’d like to reverse the process. I tried, in a very small way, to acknowledge my wife Joan’s contribution to this book — and to my life — in the dedication. But my daughters Karen and Joan, no mean writers themselves, have also been wonderfully encouraging. And, whenever I was sitting there staring at a blank sheet of paper, my son Mark instinctively showed up and took me out for a game of racquetball. At Bear Stearns, Jonathan Barnett was typically kind and supportive of my nights-and-weekends efforts to produce this book.

I literally could not have completed the task without Andrea Ricigliano. And Hoda Zahid instantly tracked down all manner of arcane statistical information, always making it look easy. Bob Stanger gave me the idea for the book; his and Keith Allaire’s fine editorial hands add much value to a manuscript that clearly showed the enthusiastic haste with which it was written. I became familiar with the work of Aaron Hemsley Ph.D. in 1983 when I took his “Psychology of Maximum Sales Production” course. Aaron’s work is specifically for financial planners and investment salespeople, and I believe it is critical to your success in the 1990s. Marvin Brown taught me to sell mutual funds twenty years ago.

More than that, he showed me that there was such a thing as “the sales process.” This book is a continuing exploration of that process, so it owes much to Marvin. In the acknowledgments for my previous book. Shared Perceptions, I thanked my friend Gordon Joblon for his critical intervention in my career. His response was the last letter I had from him before he died. I miss him and am just glad I got to say “thank you” in time. If thinking about writing a second book were the same as writing a second book, this book would have been done two years ago.

I’m grateful to Kenneth Schwartz M.D. for helping me get on with it. Finally, I think I’m a better businessman and a better investor (and even, perhaps, a little better person) because of the opportunity to work for Alan C. Greenberg at Bear Stearns for the last six years. But, of course, the beliefs, opinions and mistakes in this book are mine alone. They certainly do not necessarily reflect the opinions or business practices of Bear Stearns, which is not responsible for the content of this book in any way.

On October 19, 1987, the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell 23% on New York Stock Exchange volume of six hundred million shares. In mid-May 1989, Eastern Europe’s most honored living playwright, Vaclav Havel, was a political prisoner in a Prague jail cell. On December 29 of the same year, he was elected President of Czechoslovakia, becoming his country’s first non-Communist leader in nearly half a century. During just a few months, from the Atlantic to the Brandenburg gate, and on to Moscow itself.

Communism had virtually collapsed. In September 1989, after nearly a decade of unprecedented corporate takeover mania, the stock of UAL Corporation, parent of United Airlines, was trading at $300 per share. The company’s unions were negotiating to acquire the airline, but Wall Street was speculating that even more aggressive bidders would soon appear. No one knew it at the time, but UAL was about to become, in relation to the 1980’s leveraged buyout craze, what Pickett’s charge was to the Confederacy: the high water mark.

On the afternoon of Friday, October 13, 1989, bankers advised the unions that the acquisition of UAL at $300 per share was not financeable. Period. When the story hit the news tape, the Dow Jones Industrial Average went down 7% in two hours on huge volume. Takeover stocks — real or imagined — lost twenty and thirty percent in value. Toward the end of the day, the market in many junk bonds — Serious Money: The Art of Marketing Mutual Funds issued to finance the wave of highly leveraged takeovers — simply ceased to exist.

One year later, loans for hostile takeovers were unavailable on any terms from any traditional lender. The brokerage firm which virtually created the concept of junk debt vanished into Chapter 11. And UAL stock touched a low of $84-1/4, down 70% in thirteen months, as doubts arose that any takeover was possible at any price. In mid-July 1990, the price of oil was under $17 per barrel and falling freely. After almost four years of weak oil prices, public opinion had written OPEC off. It was seen as a cartel that had failed under the weight of oversupply.

Few people realized that four years earlier, when oil traded briefly below $10, at least a dozen of the 16 members of OPEC produced over quotas. But in 1990, only two were cheating. And one, Kuwait, began to realize neighboring Iraq was moving troops toward its border. Within thirty days, the price of oil was near $40.

All of these events, and many more, tend to drive home the lesson that the world has become too complex, and events are unfolding too suddenly, for the individual investor to function comfortably. The volatility with which markets respond to change, and the advent of phenomena like “program trading,” create an investment climate which the investor hates and fears.

The individual investor has ceased to believe he can manage his own investments. Instead, he has turned to “managed money” — investments where the individual turns his money over to someone else to manage. While mutual funds are the most common example of “managed money,” the concept embraces a broad universe of investments including variable annuities and “investment” life insurance, real estate investment trusts (REITs), closed-end funds, “wrap” accounts, and even unit investment trusts. The investor will not be back to picking individual investments anytime soon.

And, he is almost certainly correct. But will the individual investor handle his investments in managed money accounts any better than he ran his own portfolio? Will he be able to sort out the bewildering, and proliferating, variety of managed money vehicles? Not a chance. Without an adequately compensated advisor to help with selection and discipline, the individual investor will simply make all the classic, horrendous mistakes.